When we were at the Ludlow Food Festival earlier this year, I was asked by Paul Shuttleworth of BBC Radio Shropshire if I would mind coming on their Sunday morning cookery programme at some stage. Without thinking much about it and needing to fend off the crowds of customers, I said yes quickly and took Paul’s card. We then made a date for me to go in on Sunday 2nd November, having managed to find a weekend that was surprisingly clear of events, as this is a rather hectic time of year for us at the moment.

A few days ago the email arrived giving me all the details I needed to do the show, including the explanation that they have a ‘virtual fridge’ with a pineapple that ‘needs using up’, and could I come up with ideas of what to do with it…

My first reaction was that I should look rather blank when I am asked this ‘on air’, and say “what’s a fridge?”. The first commercial fridges didn’t exist until the 1850s (rather late for me). Perhaps they assumed that I was a rather wealthy gentleman (owning half a county or two) and had an icehouse? The term “refrigeratory” had been used when referring to the cooling of foods and drink as early as the 17th century, so this must be what they are talking about!

Then I panicked at the word ‘pineapple’! My immediate reaction was that they didn’t have pineapples in the 18th century, or if they did, they were only for the immensely wealthy. You hear tales of them being grown in expensive hot houses, and then just sitting in the dinning room as a centrepiece until they rot away. They were exhibition pieces, with greater value on display than being eaten. They were even rented out by the day so that they could be displayed and not eaten. What would I be able to say?

The thing that I love about my job is that I often get to disappear off on research tangents. I needed to learn more about when pineapples appeared on the dining table and how they were eaten. Thankfully I was slightly wrong, and I was able to come up with a recipe from 1736.

The first European encounter with the pineapple was, probably inevitably, Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the ‘New World’ on the 4th November 1793 (perhaps the 4th November should be Pineapple Day?). They discovered the fruit in the deserted houses of the Tupinambá people, who had fled in fear of these strange foreigners.

“They also saw calabashes and some fruit that looked like green pine cones but were much larger; these were filled with solid pulp, like a melon, but were much sweeter in taste and smell. They grow on plants that resemble lilies or aloes…”

As with so many things (including chocolate) the Spanish weren’t so keen on sharing with the English. Well… we were at war with them fairly frequently!

It wasn’t until the 17th century that the English began to get up close and personal with the pineapple. Bearing in mind that initially pineapples had to be shipped over to Europe from South America. If one were picked green and unripe, it was probably rotten by the time it arrived in Europe.

In 1640, John Parkinson – Botanist to Charles I – described the pineapple as being:

“Scaly like an Artichoke at the first view, but more like to a cone of the Pine tree, which we call a pineapple for the forme… being so sweete in smell… tasting… as if Wine, Rosewater and Sugar were mixed together.”

This comment partly explains the name ‘pineapple’, as what we now know as ‘pine-cones’ were also known as ‘pine apples’, being the fruit or ‘apple’ of the pine tree. The pineapple was thought to look a bit like a pine-cone. ‘Pine apples’ have become ‘pine-cones’, and the exotic fruit has become the ‘pineapple’ (clear?). Also the flavour being described as being like wine, rosewater and sugar immediately ranks the pineapple as being very high status and desirable. This surgery exoticness pushed the pineapple above the other exotic imports, such as the potato and tomato.

John Parkinson was describing a fruit that still hadn’t seen the shores of England, and it wasn’t until 1675 that the very first pineapple was reputedly cultivated on English soil (or is that ‘in’ English soil?). This new fruit was apparently presented to King Charles II by his gardener, John Rose, although some are dubious that it really was grown in England at that early date.

Pineapples began to be grown commercially in the 1720s, and so this exotic fruit, once the reserve of the seriously wealthy, began to filter down to the aspiringly wealthy. Richard Bradley produces what is probably the earliest published English recipe in 1736, and like buses, two recipes come along in the same book: one for a tart, and one for a marmalade. The full title of his book is ‘The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director, in the Management of a House, and the Delights and Profits of a Farm‘. Pithy lot, those 18th century writers!

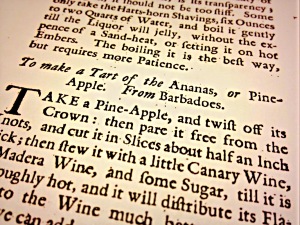

To Make a Tart of the Ananas, from Richard Bradley’s 1736 ‘The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director’.

To make a Tart of the Ananas, or Pine-Apple. From Barbadoes.

Take a Pine-Apple, and twist off its Crown: then pare it free from the Knots, and cut it in Slices about half an Inch thick; then stew it with a little Canary wine, or Madera Wine, and some Sugar, till it is thoroughly hot, and it will distribute its Flavour to the Wine much better than any thing we can add to it. When it is as one would have it, take it from the Fire; and when it is cool, put it into a sweet Paste, with its Liquor, and bake it gently a little while, and when it comes from the Oven, pour Cream over it (if you have it) and serve it either hot or cold.

The ingredients required are simply: a pineapple, some Canary Wine or Madera, sugar, and some sweet pastry.

Canary Wine was one of the commonly available wines of the 18th century, which was also known as Sack, imported from Spain and the Canaries. It is described as being a dry amber wine, occasionally sweetened with honey or sugar. In the 17th century John Evelyn writes about ‘sacke or other strong wine’, suggesting that Sack was fortified, similar to sherry. A sherry is the accepted substitute for historic recipes, and in this case I used a delicious medium dry Oloroso Sherry, which is probably one of the closest flavours to the original Sacks and Canary Wines.

The recipe states that the pineapple should basically be stripped of its outer skin, and cut into half-inch slices. It doesn’t mention whether the core is cut out, but I opted to do this. The core is edible and in fact, holds a lot of the goodness, but is tough and gritty. I also further cut the slices into smaller chunks as I was making several smaller tarts. It would be interesting to try leaving the slices whole next time.

The sweet pastry was then made up into a tart case. Tin baking containers did begin to be used during the 18th century, but 1736 is a little early for these, so a free standing pie case is more genuine. This needs to be raised by hand and carefully blind-baked to hold its shape. I tied some paper around the tart as a collar to hold the shape (brown paper was a valuable tool of the 18th century kitchen).

The pineapple chunks were then stewed in a good slug of the sherry, with about 6 tablespoons of sugar, until they are “thoroughly hot”. I probably used too much sherry, so I still have a glass of the leftover syrup to be used (or drunk).

The cooled stewed chunks were then put into the cooled pastry case, and a little of the syrup poured over, and then the tart was returned to the oven to bake for about 15 minutes.

On bringing out the tart, Bradley suggests that you can “pour cream over it, and serve it either hot or cold”. This suggests that you can add the cream to the tart whilst it is hot, and then allow it to cool. I tried this and the cream soaks into the tart, and hardens slightly, producing a delicious result!

The resulting tart is delicious with the sweetness of the exotic pineapple slightly off-set by the dryness of the sherry. No flavours are overpowering, and all-in-all it is a big success. Well done Mr Bradley, Sir!

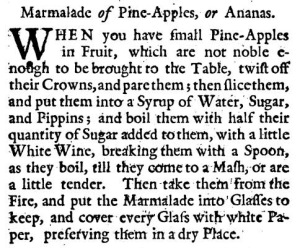

For those of you who want to go on with the pineapple story… here is the Marmalade of Ananas recipe: